Practically overnight, in spring of 2020, nearly every school teacher in America became an online teacher – whether they had ever taught online, whether they had ever had online education training, whether or not they had any idea what Zoom meant.

That was just one effect of the COVID-19/novel coronavirus pandemic, a rapidly spreading illness that ground normal life to a halt across the world and made “unprecedented” the word of 2020. From sports to retail shopping to government, from the most mundane of daily activities to the most consequential, no aspect of contemporary life was untouched, and all will very likely go on forever changed.

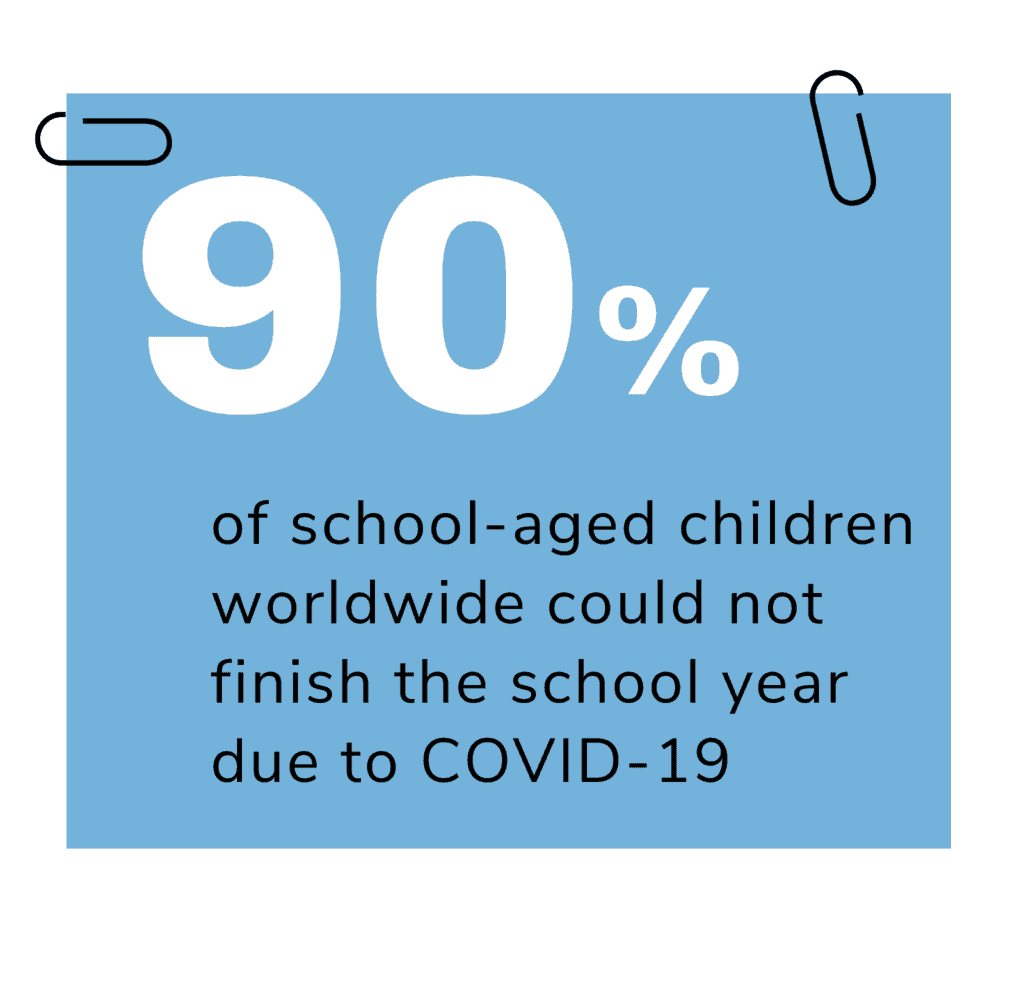

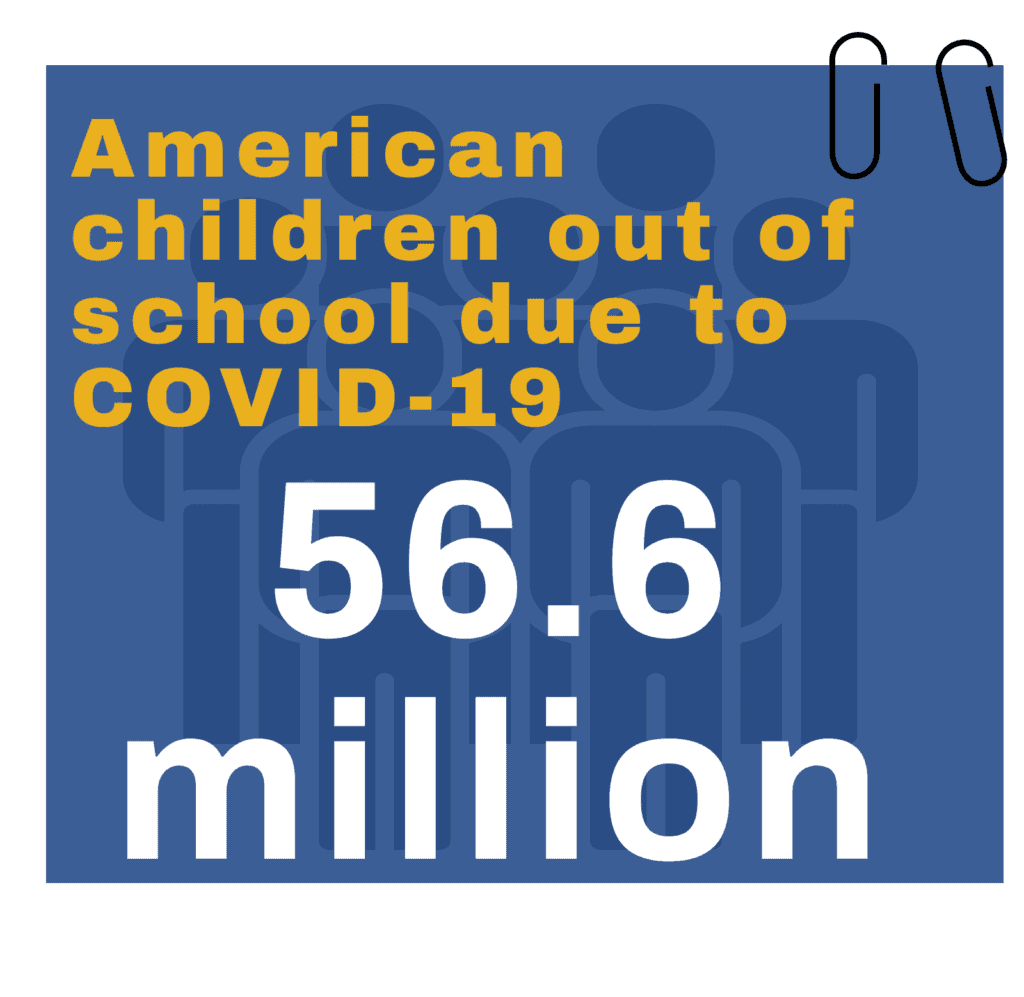

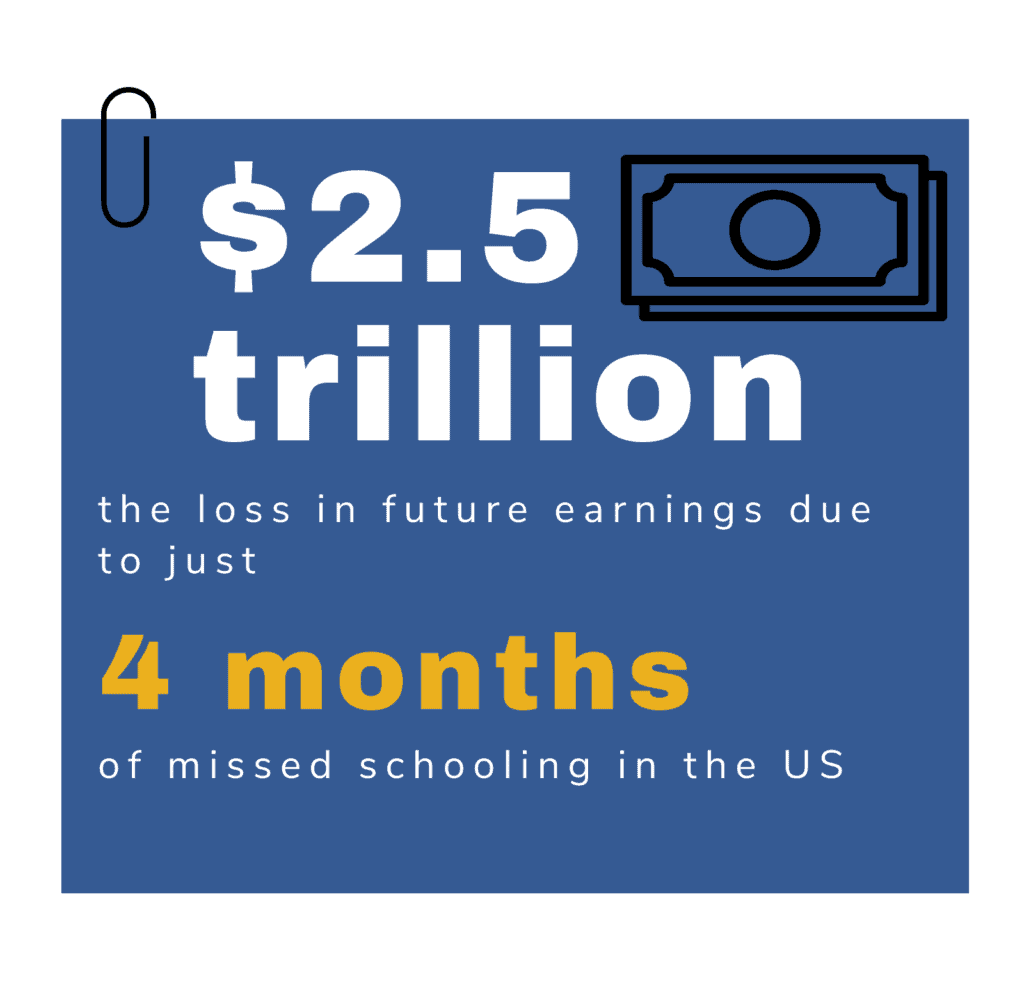

As of March 2020, all but two states in the US had closed their school systems for the rest of the 2019-2020 school year; Montana and Wyoming allowed individual school districts to make their own choices, but most of their schools closed as well. Worldwide, more than 90% of schoolchildren were out of school due to the pandemic, according to data from the Brookings Institution.

There is no doubt: education in the US will never be the same. Not only will schools across the country have to cope with a less-safe world, but teachers will have no choice but to adapt to methods of teaching and a teaching environment extremely different from that in which they learned and practiced before – even if they just graduated from college and began their career.

And it’s going to involve a lot of tech. Tech, and public health interventions.

On-Site to Online: The Big Switch

Education experts have long since been telling us that more online instruction would be the future of education – it’s just that no one expected it to come so suddenly. At the beginning of March, schools everywhere were open; by the end of the month, nearly all were closed, moving to online instruction for the remainder of the school year.

Online schoolwork has become typical in K-12 schools. Many districts have used grants or donations to supply every student with laptops or tablets, and teachers have been incorporating online work in the classroom and for homework regularly. A large proportion of professional work today is done online, after all, so primary and secondary education has to prepare students for the future of work.

But very few teachers were ready for the complete changeover, especially when it entailed completely revising their prepared curricula in just days – at most, a couple of weeks. Creating lesson plans for the classroom and creating lesson plans for virtual learning are vastly different tasks.

In other words, to finish out the school year, teachers all over the US were asked to do an all but impossible task – and they did it. Doing it has enormous implications for the future of teaching.

We All Learn Online Now

As Johns Hopkins Engineering informs its online instructors, planning for online classes must take place ahead of time and try to accommodate many kinds of learners. While teachers in the classroom can observe how students are reacting and shape their instruction accordingly, there is very little room for improvisation or adaptation in online teaching. Traditional assessment tools don’t work as well either.

But Johns Hopkins is thinking of mature, adult students. For elementary, middle, and high school teachers, being able to shape instruction to the students’ immediate needs is especially important. Good school teachers plan their lessons knowing that what actually happens in the classroom will alter them.

With children and adolescents, patience and direct attention are often crucial to helping a student “get it” in a difficult lesson. Online platforms can provide a substitute, but not a replacement.

It’s important to realize that the instructional technology that is currently widely available is relatively primitive. For kids, slide shows and group chats are not the same as direct instruction. Of course, a student can replay a video if they don’t quite grasp a concept, but the video will always be the same – the teacher can’t reword the lesson or try a different tack. Web conferencing tools like Zoom or Google Meet can approximate face-to-face instruction, but as numerous viral videos have demonstrated, online video conferencing can be chaotic even with small groups of adults – much less 15-20 third graders.

Complaining about the shortcomings of online instruction doesn’t change the fact that, thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, online instruction is here to stay. Even the most optimistic predictions do not expect a vaccine or cure until 2021 at the earliest, which means that even if schools reopen in the fall, we can expect further waves of infection that will force schools to close for short but fairly regular intervals. When an outbreak happens in a school district, they will have little choice but to close for 2-3 weeks to cut down the spread.

That means teachers will always have to have a contingency plan lined up for every unit. A “pandemic plan” for every class. Even after the coronavirus is squashed, there is little reason to believe we will go back to “normal.”

Teaching Teachers Now for the Future

So from now on, teachers and education students will have to have extensive training in online instruction. Online teaching will have to become a basic part of teacher instruction, no matter what kind of education degree future teachers are getting.

Special attention will have to be paid to the most vulnerable students as well:

- Early childhood and elementary education

- Special education

- Low-income and disadvantaged students

All of these categories present important challenges to online teaching that all teachers will have to be prepared for, either with mandatory continuing education, or in their education degree programs.

Early Childhood/Elementary: Young children, especially preschoolers, have difficulties learning online. In early developmental stages, human contact is key. Online learning can provide valuable reinforcement of skills, and as PBS Newshour reports, it’s better than nothing, but online instruction for small children must be carefully designed to accommodate children’s learning. For future early childhood and elementary teachers, developmentally appropriate online curriculum development will have to be emphasized.

Special Education: Students with physical disabilities or learning disabilities are at a particular disadvantage with online learning. Children and young people with visual or hearing impairment may struggle to learn from an online source. One-size-fits-all online instruction threatens to leave students with learning disabilities behind. Many researchers are developing technological solutions to help with disabled students, but these will have to immediately become part of mainstream teacher education.

Low-Income Students: Students in underprivileged school districts have far less access to technology than students from middle-class or wealthy suburbs. While the gap is normally thought of as affecting rural communities, low-income urban communities also lack the access to broadband internet that makes online learning possible.

New teachers and experienced teachers alike will have to learn to take these challenges into account. With the need to take learning online due to the pandemic, the need for expertise in online teaching will cross specializations and age groups.

How to Make Classrooms Pandemic-Safe for Fall

At the time of this writing, school systems across the US are still up in the air about the probability of opening up again in the fall. In some states, officials have confidently asserted that schools will be open just as usual; others have cautiously warned parents to expect online classes, or more limited school days. Public health experts have warned of a second wave in the fall that could once again close schools.

The issue of opening schools is particularly important because many children who catch the coronavirus are asymptomatic spreaders. Children under 18 made up less than 2% of COVID cases, despite making up 22% of the population, and aside from the still-mysterious inflammatory illness, most children exhibited light or no symptoms. Infants are more likely to be severely ill to the point of hospitalization. That all means, however, that school-aged children can be carriers without ever knowing they are infected – but could infect teachers and staff, as well as bringing the coronavirus home to parents and elderly relatives.

There are innumerable considerations involved in reopening schools, and there is no doubt that American education will look radically different in the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year than it looked in 2019. When it comes to the safety of students, teachers, and staff, the first and foremost considerations are how to pandemic-proof schools. That will include:

- Antibody Testing

- Funding for PPE

- Smaller class sizes for social distancing

- Increased sanitation

All of these provisions are daunting, for their own reasons, but to realistically open schools in the fall, they are critical. Taken altogether, they illustrate how different teaching will be in the future.

Testing for Teachers and Staff

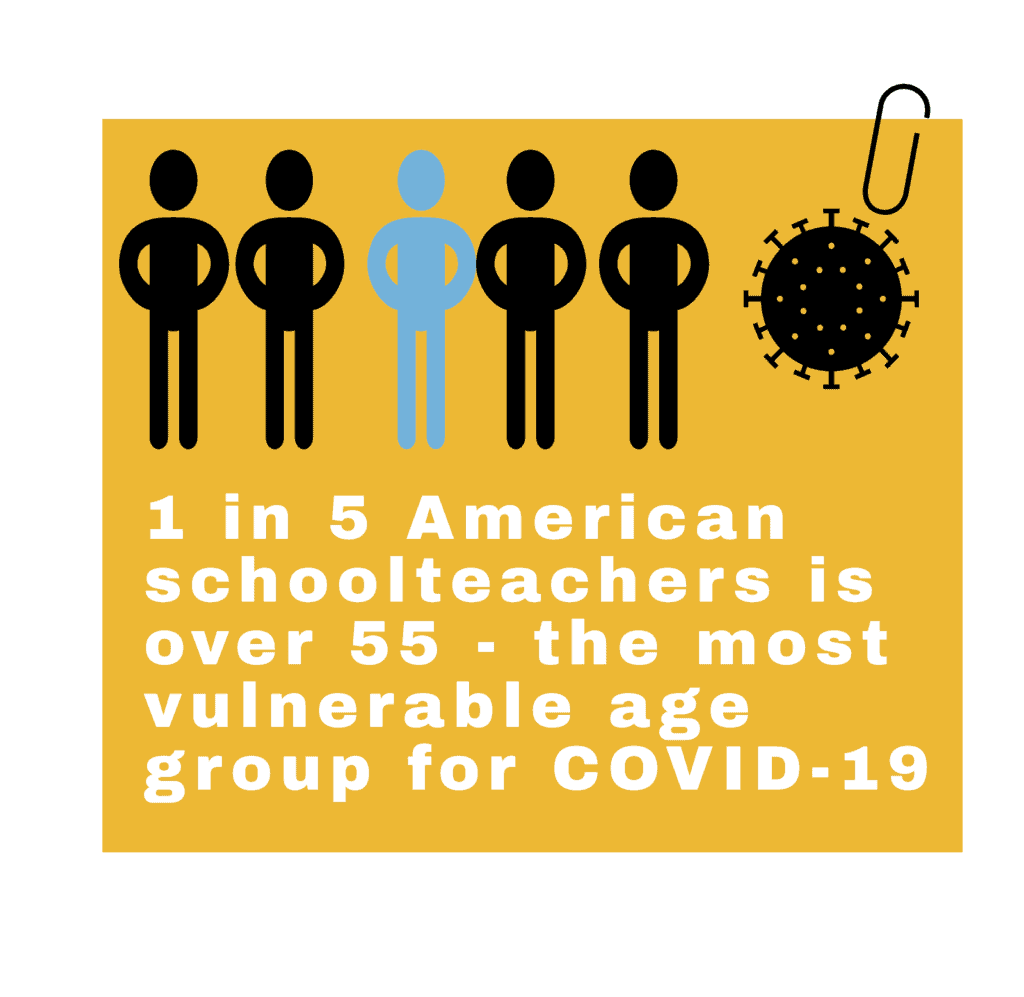

The American Enterprise Institute – one of the most influential neo-conservative think tanks in America – issued an extensive report titled “A blueprint for back to school,” outlining necessary action for governments and school administrators in order to actually open schools in the fall of 2020. Among the most important points in the report is the realization that a fifth of teachers and a quarter of principals are over the age of 55 – the age group most likely to die from COVID-19.

This is serious. It means that many of the most critical leaders in the school system – the most experienced and influential teachers and administrators – are also the most vulnerable.

This places educators in a tight spot. Very likely, many of those who are vulnerable and will choose to retire, if they have sufficient years in the system, or will make the difficult decision of starting a safer, alternative education career.

For that reason, in the absence of a vaccine, many experts have called for a priority on antibody testing for teachers, to determine whether they are safe from infection due to having already had the virus. Some have even suggested restricting classroom instruction to only those who have had COVID-19 and recovered, and moving vulnerable teachers into other roles or online. “Safe” teachers, in this scenario, would have to be identified with testing and set apart in a way that does not violate HIPAA guidelines.

Unfortunately, in the US lack of access to tests – as well as shortages in reagents, swabs, and testing machines – has meant that testing has been severely underutilized. Long delays in processing results has meant positive cases have gone undetected for days, while they could still spread the virus. Most areas of the US have been unable to even test all medical workers, much less schoolteachers. And to add to the problem, American public health departments have nowhere near the number of contact tracers necessary to follow through on identifying and isolating the spread.

One of the most important parts of getting schools back on track, then, is hampered by lack of critical knowledge:

- Who is sick

- Who is safe

Until those facts can be established, opening schools is inherently risky.

Personal Protective Equipment for Educators and Students

A shortage of personal protective equipment for staff in hospitals and other medical facilities was one of the most persistent scandals of the pandemic. In the hardest-hit areas, nurses were forced to use the same masks – designed to be disposable – for as much as a week, disinfecting the disposable masks until they began to break down. Nurses across the US protested for more PPE. The federal government began seizing shipments of PPE as the supply chain broke down, and drastic measures were taken:

- The governor of Maryland’s Korean-American wife negotiated directly with a Korean company for PPE when more conventional procurement fell through

- The governor of Illinois had PPE flown in on secretly chartered planes

- In Michigan and Oregon, the National Guard was called in to protect stockpiles

When the CDC began recommending that all Americans wear face masks when going out in public, a cottage industry of mask-making boomed on Etsy and Ebay. And the nonprofit group GetUsPPE continued to raise the alarm that a vast majority of healthcare facilities were perilously close to running out of masks, gowns, and gloves.

So when the American Enterprise Institute recommends that teachers and staff be fully equipped with PPE in order to reopen schools, it begs the question:

Where, pray tell, will schools get PPE?

It is clear that for schools to reopen safely, all involved – students, teachers, and staff – will need personal protective equipment. Who will be responsible for it, however, is another matter.

All over the US, school budgets are strained and inadequate. Teachers are already known to use their own money to buy supplies; will they be forced to buy face masks for their students as well if the school cannot afford it? Will low-income students have to make do with less effective alternatives like handkerchiefs, while higher-income students provide their own N95 masks?

These are significant issues that teachers will need to be prepared for when they return to their jobs in the fall.

Social Distancing in Overcrowded Classrooms

School overcrowding was a serious issue before COVID, but without a vaccine or herd immunity, overcrowded schools will be one of the primary sites for spreading an outbreak – that’s why, in most states, schools were closed before restaurants or stores.

Between a quarter to a third of schools in the US are overcrowded, depending on how overcrowding is defined; based on a widely-recognized ideal of 15 students or fewer per class, a much higher percentage would be considered overcrowded.

Can we compare schools to restaurants? Restaurants can

- operate at 50% capacity

- seat customers more than 6 feet from the next table

- and even put up barriers between tables

They won’t make as much money, but they will stay in business. Public schools, on the other hand, cannot turn away students. They cannot quickly construct new schools to increase capacity. Short of putting each student into their own isolated cubicle, separating desks will not be a simple option.

Overcrowded schools mean that giving students the CDC and WHO recommended distance of 6 feet (2 meters for the rest of the developed world) will be simply impossible.

The classrooms aren’t the only problem. Cafeterias, locker rooms, even hallways are areas where students are unavoidably too close together. Providing students with adequate social distancing to avoid infection and spread will mean revising everything from how students change classes to physical education classes and after-school sports. Many conventional school activities now carry a risk never before contemplated.

How this problem will be solved remains an open question. The Supreme Court has affirmed again and again that all American children have a right to a public education. Furthermore, health information is strictly confidential under HIPAA rules. Any arrangement that smacks of “separate but equal” – such as dividing classrooms into COVID and non-COVID classrooms – will undoubtedly be challenged.

Sanitizing the Schools

Hear us out: schools are filthy places. That is not casting blame. Children and adolescents, by and large, are not known for their impeccable hygiene, or for their awareness of how their actions and behavior affect others. And squeezing many young people into one location means that location will, inevitably, be more than a little germy.

Teachers do their best, custodians do their best, and kids do what they do, but the need for sanitization from the novel coronavirus goes well beyond the usual cleaning and tidying. Coronovirus can live on surfaces for days, and the surfaces in schools that are touched, coughed and sneezed on, and touch again include – well, pretty much all surfaces.

Keeping reopened schools clean will mean sanitizing the school nightly, in a much more vigorous way than taking out trash and wiping down tables. That, in turn, will mean a need for more custodial workers, and more protective equipment for them as well. This will also mean changes in scheduling; no more evening activities, when custodians need to be cleaning. For the same reason, after-school activities – which many parents count on for childcare – will have to be cut down.

There are also strong recommendations for switching to year-round schooling. Most schools in the US still run on a traditional summers-off calendar, rooted in an old agrarian model, despite the fact that:

- Farm families make up less than 2% of the population

- Most schools are air-conditioned and need not be disrupted by hot summers

In a pandemic environment, a nationwide switch to year-round school would be helpful for other reasons besides higher learning-retention rates and alleviating the problem of summer childcare. Shorter terms with 2- or 3-week breaks would allow for more thorough cleaning in the off periods, and time in which the school can sit unused while viruses left on surfaces could die off. Experts have already warned that schools will need to be prepared to close for a few weeks at a time in response to new outbreaks; a year-round schedule would build these closures in.

So What Will Teaching in a Post-COVID World Look Like?

We said at the beginning that teaching in the fall of 2020 will look nothing like teaching in the spring of 2020. No teacher – grizzled veteran or new spring of 2020 graduate – has had the training or experience for it.

So if schools are able to open in the fall, what will it look like? It might look like:

- Teachers, staff, and students wearing face masks at all times

- Seats spread as far apart as physically possible

- Teacher distanced from the class – possibly even with plexiglass walls

- More strictly structured lunchtimes, hallway traffic, and socializing

- The end of Phys Ed as we know it (especially locker rooms)

- Fewer, if any, after-school activities

- More intensive cleaning

And if further waves of infection keep schools from opening, or force them to close periodically, it means:

- Getting more creative with distance learning

- Jumping back and forth between in-class and online instruction

- More interventions for special needs and low-income students

There is no easy solution. Wishing will not make a pandemic go away. But with proper preparation, training, and accommodations on the part of teachers and schools, the COVID-19 pandemic and all of the social disruptions it causes will not have to set our children back. The pandemic will unavoidably shape how today’s children see the world, but it can also be an opportunity for education to make a quantum leap into the future. It all depends on how we as a society support our teachers and students.

Related Rankings:

- 25 Best Online Associate’s in Early Childhood Education

- 25 Best Online Bachelor’s in Early Childhood Education

- 25 Best Online Master’s in Early Childhood Education

- 25 Best Online Bachelor’s in Elementary Education

- 25 Best Online Master’s in Elementary Education

- 25 Best Online Bachelor’s in Special Education

- 25 Best Online Master’s in Special Education